|

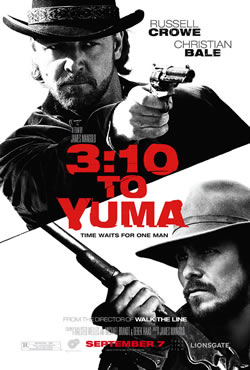

Reviews The West Revisited: On 3:10 to Yuma and The Assassination of By Jack Baur and Jamie Hancock At the tail end of this last year, the movie world was witness to a minor renaissance of the classic Western. Two films, 3:10 to Yuma and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford sprang from out of nowhere, starring some of Hollywood’s best actors and reminding us that the Western still has a lot of blood left in it… figuratively and literally. To assess the impact, resident film reviewers Jamie Hancock and Jack Baur come at you with another two-fisted review double-feature.

The simplicity of this plot belies the tension, suspense, and power of 3:10 to Yuma (at least the first two-thirds of it). In fact, simplicity is a large part of the film’s success. The film wastes no time getting into the action, opening with an explosive stagecoach heist by Wade’s gang, followed swiftly by Wade’s capture. After a minimal amount of plot set-up, the crew is on their way to the train, crossing through a majestic landscape where danger lurks everywhere. This journey, which makes up the film’s extended second act, ratchets the tension to an unbearable degree thanks to excellent pacing (no sooner do you think things are safe than the bullets are flying again) and the film’s refusal to pull any punches. Credit is also due to fine acting all around, particularly by Crowe and Bale. Crowe, who I normally hate1, offers a brilliant performance. His Ben Wade is terrifying – a lawless monster made all the more dangerous by his charm. He can seduce with a smile, kills in a blink, and takes whatever he wants. By contrast, Bale’s Dan Evans is a man of integrity that has been physically and spiritually broken by life and who sees taking on this impossible mission as the only way to redeem himself to his family and forgive himself for past mistakes. He’s the only one who is completely immune to Wade’s charms, and Wade seems to respect Evans’ stubborn integrity. The dynamic between these two strong characters elevates the film even further beyond the superb thriller that it already was, also presenting the two competing ideals of the standard Western Mythos: lawlessness and righteousness. These ideals come head-to-head, embodied in two characters that understand and respect each other, each a little more than they want. This trick serves to heighten the film’s tension while expanding its intellectual palette. For awhile, 3:10 to Yuma is not just a great Western in the classic tradition, but a great film all around. Unfortunately, the dramatic tension between the two leads falls apart in Yuma’s last reel, as a fatal dose of testosterone is injected directly into the film’s gonads. The delicate balance between Wade’s charismatic sadism and Evans’ wounded nobility is subsumed by an ideal of masculinity that is only concerned with how many bullets are in your gun. The suspense that had been building throughout the film explodes in a climax of bravado that is as pointless as it is, ultimately, obvious. By the third act we have heard Evans go on about the righteousness of his task and his determination to prove himself so often that we already see that there’s only one way the movie can end. The fact that that how it must end is, in fact, how it ends is a little disappointing. Still, even if this final bout of bloodletting is a letdown, this is not a movie to be ignored. Even if you don’t normally count yourself as a Western fan, the quality of the filmmaking on display here should be enough to make you a believer. It’s just too bad there can’t be more to being a man than killing a whole lot of people. In contrast to Yuma’s thunderous sound and fury, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford is a meditative take on the Western. If Yuma’s characteristic scene is Wade and Evans blasting their way through a town, Assassination’s characteristic scene is a static shot of Jesse James (played by Brad Pitt) standing mesmerized watching a field burn, or suddenly illuminated by the light of a train that he intends to rob. This is another story of two men pitted against each other in the unforgiving West, and its impact is just as intense. But Assassination is a slow bruise to Yuma’s bloody nose.

Overshadowing Brad Pitt’s performance, however, is Casey Affleck’s personification of Robert Ford. Affleck plays a bumbling, naïve nineteen year-old who longs to become Jesse James, or at the very least, become a close friend to the famed bank robber. In this role, Affleck captures the essence of both social awkwardness and hero worship. Following James’ last train robbery, the bright-eyed, young bandit is eager to impress both of the James brothers, and it’s obvious he’ll do anything to become a permanent fixture in the gang. Ford’s childish manner is wonderfully exhibited in his rambling conversations that are peppered with awkward silences and occasional glances for approval. Roger Ebert has suggested that Ford had a homoerotic fascination that could only be satisfied by the death of his hero. I would not go quite that far. I would liken it more to the following situation: an adoring minor leaguer meets Barry Bonds, finds out he’s a jerk who does steroids, and then resorts to something drastic to reconcile his huge shift in perception, and realizes he can gain from harming his idol. This movie does a fantastic job of showing the changing perspectives of a doting star-stalker and how he becomes an improbable assassin. The film’s greatest triumph is its aversion to the traditional Western formula. In his attempt to explain the final events of the legend’s life, director Andrew Dominik focuses his lens on the characters, how they think, feel, and relate to each other. In this respect, the actions of the story are completely secondary to the personalities of the characters. When we sat down into our theater seats, we all knew what was going to happen – Brad Pitt is going to be killed. This movie somehow made me forget about the ending temporarily and it made me want to explore the lives of James and members of his gang. Besides the twisted relationship between James and Ford, the film features interesting subplots, including the traitor Dick Liddil’s (Paul Schneider) feud with fellow outlaw Wood Hite (Jeremy Henner) over an adulterous act, and Ford’s relationship with his older brother, Charley, played brilliantly by Sam Rockwell. I should also mention that this film is beautifully framed, which should be no surprise – it was shot by cinematographer Roger Deakins, who received an Oscar nomination for “No Country for Old Men.” So far, the criticisms I’ve heard about this movie is that it’s too long (2 hours and 40 minutes) and that it has annoying narration. Those sound like comments from people who either don’t like Westerns or prefer them in spaghetti form.

---------------------------- 1 An Oscar for Gladiator? Puh-leaze! You’d think the Academy had never seen anybody shout a stubbornly patriotic speech, grunt once or twice, and fight a cheesy CGI tiger before! And an Oscar nom for A Beautiful Mind? Why? Alright, so the guy was a delusional paranoiac: acting involves more than just following the script! Man, celebrating this drivel is more boring than giving Tom Hanks the Oscar for Forrest Gump (don’t get me started…)

|

April 7,

2008

|

The “3:10 to Yuma” referred to in the title of director James Mangold’s (Walk the Line, Girl Interrupted) Western/thriller is a train that is going to send the West’s most notorious varmint (Ben Wade, played by Russell Crowe) up the creek to his doom. In order to get him on that train, The Law has enlisted the aid of a disgraced Civil War veteran (Dan Evans, played by Christian Bale) with something to prove to his family and to himself. Evans’ mission is to escort the captured Wade across the prairie and make sure he’s on that prison-bound train. However, along the way they’ll both have to face off against bloodthirsty mercenaries, greedy slave-traders, pissed-off Indians, and Wade’s old gang, none of whom would mind seeing Evans dead…

The “3:10 to Yuma” referred to in the title of director James Mangold’s (Walk the Line, Girl Interrupted) Western/thriller is a train that is going to send the West’s most notorious varmint (Ben Wade, played by Russell Crowe) up the creek to his doom. In order to get him on that train, The Law has enlisted the aid of a disgraced Civil War veteran (Dan Evans, played by Christian Bale) with something to prove to his family and to himself. Evans’ mission is to escort the captured Wade across the prairie and make sure he’s on that prison-bound train. However, along the way they’ll both have to face off against bloodthirsty mercenaries, greedy slave-traders, pissed-off Indians, and Wade’s old gang, none of whom would mind seeing Evans dead… Being an outlaw in the nineteenth century is a dirty, gritty business. I am not referring to the low quality of dental care, as exhibited by Luke Wilson’s character in 3:10 to Yuma. Nor am I talking about the haggard beards, the dusty towns, or the lack of bathing and indoor plumbing. Like a contemporary gangster, the success of a frontier bandit is dependent on his ability to mete out severe punishment to those who stand in his way, whether they are bank clerks, lawmen, or friends. In The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, Brad Pitt plays the cunning and sometimes ruthless leader of the James gang. Similar to many Hollywood depictions of outlaws, Pitt’s character is bold, reckless, hungry for glory, and not above murdering dishonest associates. But the movie also presents James as a jovial and happy-go-lucky family man, who is extremely likable, occasionally lonely and brooding, and increasingly wrought with paranoia and fear of betrayal. Pitt does a fine job of piecing together these various character traits and giving us a comprehensive portrait of Jesse James, who is venerable yet vulnerable.

Being an outlaw in the nineteenth century is a dirty, gritty business. I am not referring to the low quality of dental care, as exhibited by Luke Wilson’s character in 3:10 to Yuma. Nor am I talking about the haggard beards, the dusty towns, or the lack of bathing and indoor plumbing. Like a contemporary gangster, the success of a frontier bandit is dependent on his ability to mete out severe punishment to those who stand in his way, whether they are bank clerks, lawmen, or friends. In The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, Brad Pitt plays the cunning and sometimes ruthless leader of the James gang. Similar to many Hollywood depictions of outlaws, Pitt’s character is bold, reckless, hungry for glory, and not above murdering dishonest associates. But the movie also presents James as a jovial and happy-go-lucky family man, who is extremely likable, occasionally lonely and brooding, and increasingly wrought with paranoia and fear of betrayal. Pitt does a fine job of piecing together these various character traits and giving us a comprehensive portrait of Jesse James, who is venerable yet vulnerable.