Comics in the Library?:

Why Librarians should Promote Graphic Novels in their Libraries

By Pete Adelman

In the last ten years or so, the graphic novel (1) has taken its place

in many library collections. These comic (2) collections have a great deal

of potential that goes unrealized. One reason for this is that most librarians

have little

familiarity with these materials. And though library literature does note

a few possible uses for graphic novels, it leaves out many others. To make

full use of any collection, a librarian must know something about it. The

argument that comics are for kids makes little sense when considering other

resources in the young adult area. A good young adult librarian can reasonably

be expected to have read something by Walter Dean Meyers or any of several

other popular authors. How is it that librarians could have become so ignorant

about an art form that is apparently wildly popular? (3) Much of the answer

lies in the history of the medium.

Starting in the early 1930s, and especially with the introduction of Superman in 1938, comic books were an important part of popular culture. Their

readership included large numbers of boys and girls, as well as more

than a few adults.(4)

So how did they go from an accepted, mainstream format to one so little

known or poorly accepted that they were only rarely found in libraries

ten years ago?

The “Golden Age” of comics was the period prior to World War II. Sales of comics were in the tens of millions range. After the war, comic books, which at that time were mostly of the super hero genre, began to lose readership. In an attempt to increase readership, some publishers that had produced super hero books switched to other genres. Two that proved quite popular were crime and horror, both featuring realistic violence. The public backlash against these subjects was severe. One of the most important driving forces behind this upheaval was the psychiatrist Fredric Wertham. During the late 1940s, Dr. Wertham published several articles critical of the comics industry. Combined with skillful manipulation of the media and the 1954 publication of his book, Seduction

of the Innocent, his campaign generated so much public outrage that it lead to congressional investigation of the comic book industry. This public outcry was one of the most important reasons that comics lost their place in mainstream media. (5)

Rather than accept government censorship, the comic book industry banded together to form a code for self-policing. The 1954 Comics Code, adopted by the Comics Magazine Association of America, established strict standards for the depiction of crime, authority figures, religion, weapons, violence, sex, and marriage. While it allowed the industry to avoid a confrontation with the government, it was so restricting that it damaged the quality of stories that could be told.

A logical question at this point would be why libraries would ever want to collect these materials. Beginning in the 1980s, a combination of changes in distribution reducing the financial risk to publishers (6), influence from high quality foreign publications, and erosion of the Comics Code allowed by distance in time from the days of Seduction

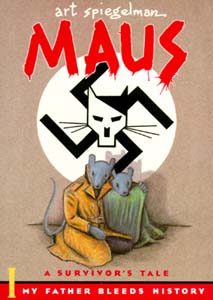

of the Innocent led to a dramatic improvement in the kinds and quality of books being produced. The comics industry began publishing several high-quality works. The most important of these was probably the Pulitzer winning Maus:

A Survivor ’s Tale by Art Spiegelman that described his father’s experiences in a Nazi internment camp. (7)

Another difficulty for librarians in understanding their graphic novel collections is that comics are read differently than books. They are not read left-to-right, top-to-bottom. Instead, the action flows from panel to panel in a variety of ways. The illustrations are an integral part of the story, and have their own rules and conventions. It is necessary to understand the pictures in order to fully understand the text.

Common conventions in comics may be confusing to those unfamiliar with the medium. The use of a series of punctuation marks to indicate cursing (@#$%), the use of “speed lines” to indicate movement, the convention of adding a panel that appears to be a non sequitur to add emphasis (“BANG” to indicate a loud noise or a frame of one character hitting another over the head with a giant mallet to denote anger) are all confusing to the casual reader. Owing to the history of the medium as unsophisticated fringe material, most librarians are at best casual readers of comics.

To make full use of a graphic novel collection, a librarian must first have

some understanding of it. A number of tools exist to make this easier.

Several quality websites are available. No

Flying, No Tights and Comics

Get Serious have good collections of reviews that can help a librarian

get started. A good book about comics can also be useful. Scott McCloud’s

Understanding Comics (8) is a graphic novel written to describe how

the comics format works. Personal advice can often be had from a local

comic shop owner.

A librarian must also know the group to be served. Graphic novels have

traditionally been seen as useful with reluctant readers, especially

boys ages 12 to 14. With new publications that handle broader topics,

the audience

is changing. According to Ellis and Highsmith, “the appeal to adolescent

power fantasies remains, but other interest has broadened considerably.

Several contemporary series appeal to women and girls…” (9) This is not

to say that girls don’t want power fantasies, but they might identify with

a different sort of character, a female one, for a start.

Libraries can serve their patrons by helping them form connections with other organizations and individuals with similar interests. A librarian that has knowledge of local events about comics; local comic publishers, artists, or writers; fan websites, and other online forums can help their patrons make these connections. Aspiring young artists may become interested in drawing comics. Writers may get interested in scripting them. The library can support these efforts by sponsoring workshops, again through the librarian’s knowledge of the local art, writing, and publishing world.

With the introduction of the World Wide Web, comics have gone online. To a librarian with knowledge of web publishing and free web server providers, the possibilities are enticing. It is possible to run a series of workshops introducing cartoonists to online publishing. And because many web comics are free, the library can easily develop an online comic collection by adding a page of links to their site.

The exciting thing for a librarian with a graphic novel collection is the combination of the collection’s possibilities and its popularity. With a bit of research and work on the part of the librarian, the collection could become the genesis for a colorful and popular young adult program.

Notes:

1. Graphic novels are generally considered bound volumes that contain

integrated stories using cartoon imagery. Comic books are magazines,

often thirty-two pages in length, using cartoon imagery. Trade

paperbacks are bound collections of comic books. For the purposes

of this paper,

the three terms are used interchangeably.

2. The term “comic” derives from the fact that the very

earliest comics in the United States (Funnies on Parade, 1935)

were supposed to be funny. The term has since come to mean any story

told

with “sequential art.” See: McCloud, Scott. (1994). Understanding Comics. New York: Harper Collins.

3. As an example, the Natrona County Public Library in Casper, Wyoming

has a graphic novel collection of approximately 120 volumes. On

average, at least 80% of that collection is charged at any given

time.

4. Ellis, A, Highsmith, D. (2000). About face: comic books in

library literature. Serials Review, 26(2), p.21-43. Retrieved October 20,

2003 from LISA database. This article details the history of the

comics industry from the 1930s through the 1990s.

5. The comics industry has a long tradition outside the United States,

notably in Western Europe and Japan. These comments apply only

to this country.

6. Schreiner, Dave. (1994). Kitchen Sink Press: The First 25

Years. Northampton, MA: Kitchen Sink Press. This change in distribution

is generally attributed to Phil Seuling who suggested creating

distributors who specialized in comics only. Their distributions

would not be

returnable, thus allowing publishers to tailor their print runs

for a known volume of sales.

7. Spieglman, Art. (1986). Maus: A Survivor’s Tale. Pantheon

Books.

8. McCloud, Scott. (1994).

9. Ellis, A, Highsmith, D. (2000).

|

Maus:

A Survivor ’s

Tale

by Art Spiegelman

|