0 2025/spectral-1031 the spectral theorem - by agastya ravuri

What the heck is a symmetric matrix?Post by Agastya Ravuri (aravuri@andrew.cmu.edu)

Ideally, this post would be targeted at those who have just learned the basics of matrices and linear transformations in a first linalg class and are maybe just about to see the spectral theorem for symmetric matrices, or at someone who has seen the spectral theorem before but felt like they didn’t understand what it was really saying (me).

If my explanation of dual spaces/covectors ends up being too confusing, eigenchris’ Tensors for Beginners series is a great resource.

Finally got this done on the most spectral night of the year.

Motivation

Usually, when you hear someone state the spectral theorem, it’s something like the following: If I have a symmetric

- It has

- It can be diagonalized by an orthogonal matrix (i.e, a rotation or a reflection); in other words, its eigenvectors are orthogonal.

When generalized to a complex matrix, we talk about a Hermitian (conjugate symmetric)

- It has

- It can be diagonalized by a unitary matrix (a matrix that preserves the complex dot product). In other words, its eigenvectors are “orthogonal.”

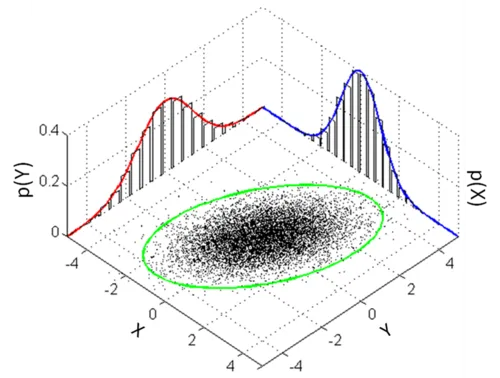

These turn out to be very useful statements: the spectral theorem is the reason why a multidimensional normal distribution will always have perpendicular major axes:

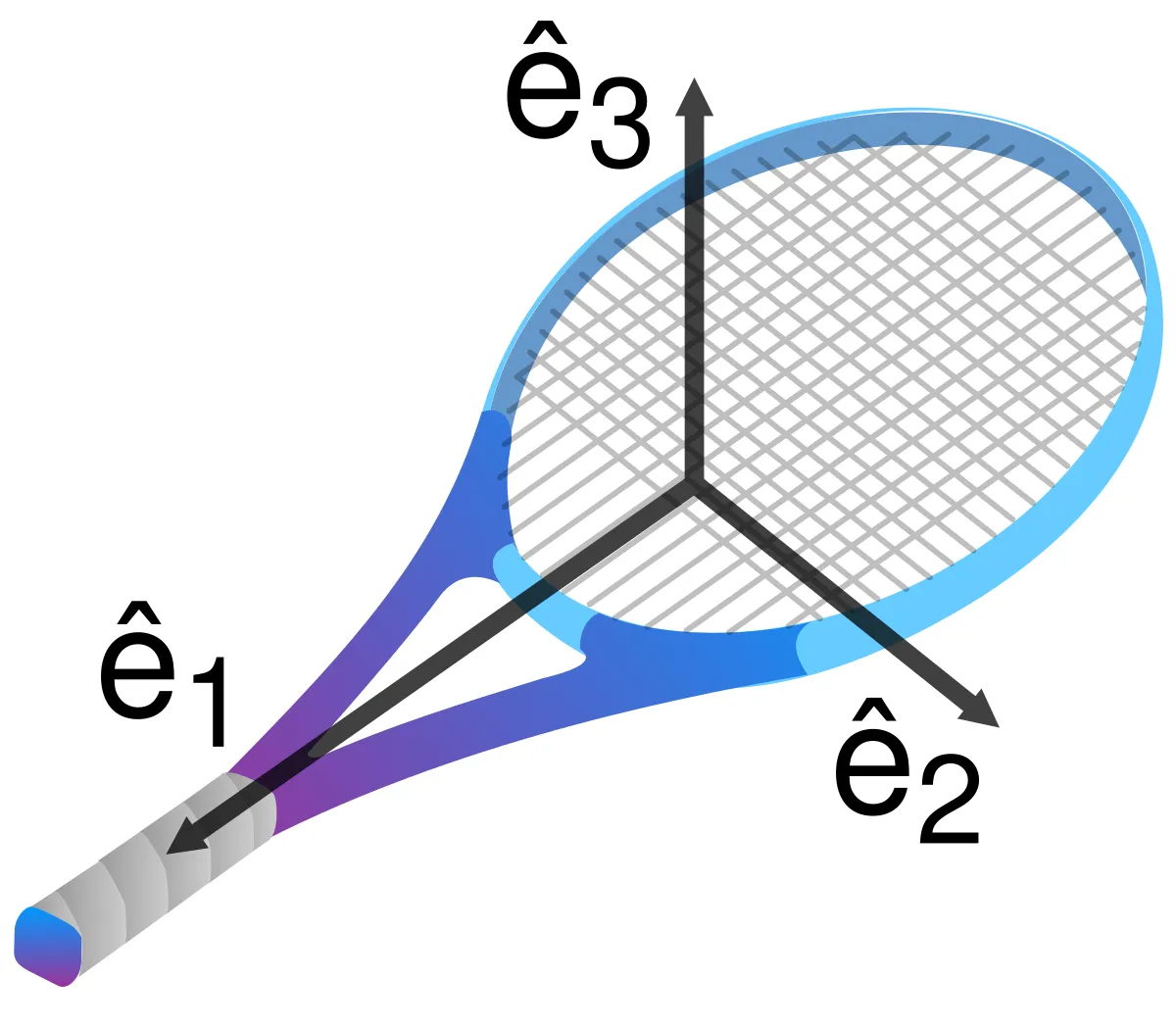

It’s the reason why all physical objects, no matter how weirdly shaped, will always have three perpendicular principal axes they rotate around.

It’s the reason why, for any (reasonable…) periodic function, I can write it as the sum of sine waves, and I can make that basis of waves orthonormal.

It’s the reason why all the quantum mechanical measurement operators have really nice properties, like how all their eigenstates are orthonormal (i think that one’s kinda reversed from the others because we defined it like that, but…).

With all these uses, the spectral theorem really starts to live up to its name: like a spectre, it influences many things we do from behind the scenes, and yet no mortal mind may comprehend what it means.

I would argue that the core of this confusion, at least for me, lay in the fact that I didn’t really know what a symmetric matrix was. To me, the spectral theorem said that this arbitrary class of matrices has an eigenbasis of orthogonal vectors. That’s a pretty cool property, but why would a matrix representing some linear transformation I randomly come across happen to be symmetric?

Overall, I want this post to bridge the gap between two intuitions for the spectral theorem, so keep these in mind:

- The eigenvectors from the spectral theorem have something to do with maximization in a direction: For example, the principal axes of rotational inertia of an object are the directions with the maximum and minimum resistance, and the directions of these axes are the maximum and minimum covariance—can this be generalized?

- The eigenvectors from the spectral theorem are orthogonal.

It turns out that both these properties are intimately related to the dot product, or, more generally, a dot product—as we’ll see, you can’t define “maximized in a direction” or “orthogonal” without it. This post seeks to give a deeper understanding of what a dot product is, and seeks to explain the “symmetric” property in that context. We will see how the spectral theorem is really a statement relating two dot products, and then present what is effectively the standard textbook proof of the spectral theorem except with this context in mind.

Note: this post will only talk about the spectral theorem for real symmetric matrices, which is its most used form; I assume there’s a similar argument for all normal matrices (the full class of unitarily diagonalizable matrices), but it’s probably more involved.

Dot Products

In

but there are two problems with this definition.

First, this definition is basis-dependent, and we don’t really like that. If I was using a different basis of

then notice that

which doesn’t match up.

A lot of the time we find that it’s simpler to work in a weird basis, but the cost of this is that the dot product might not work how it normally does.

Second, the dot product is a way of encoding similarity between vectors: it’s positive when they’re aligned, 0 when they’re perpendicular, and negative when they are misaligned. However, we sometimes find that there are two different useful ways of thinking about similarity, and if you choose a basis where one of them is the standard dot product, the other looks completely screwed up.

Instead, then, we say that a dot product is a “positive-definite symmetric bilinear form.” Let’s go through what this means in reverse order, with

- Bilinear form: A function that takes in two vectors and returns a scalar and is linear in both arguments:

- Symmetric: For all vectors

- Positive-definite: For all

When looked at like a product, these properties correspond to the distributivity of multiplication, commutativity of multiplication, and trivial inequality respectively.

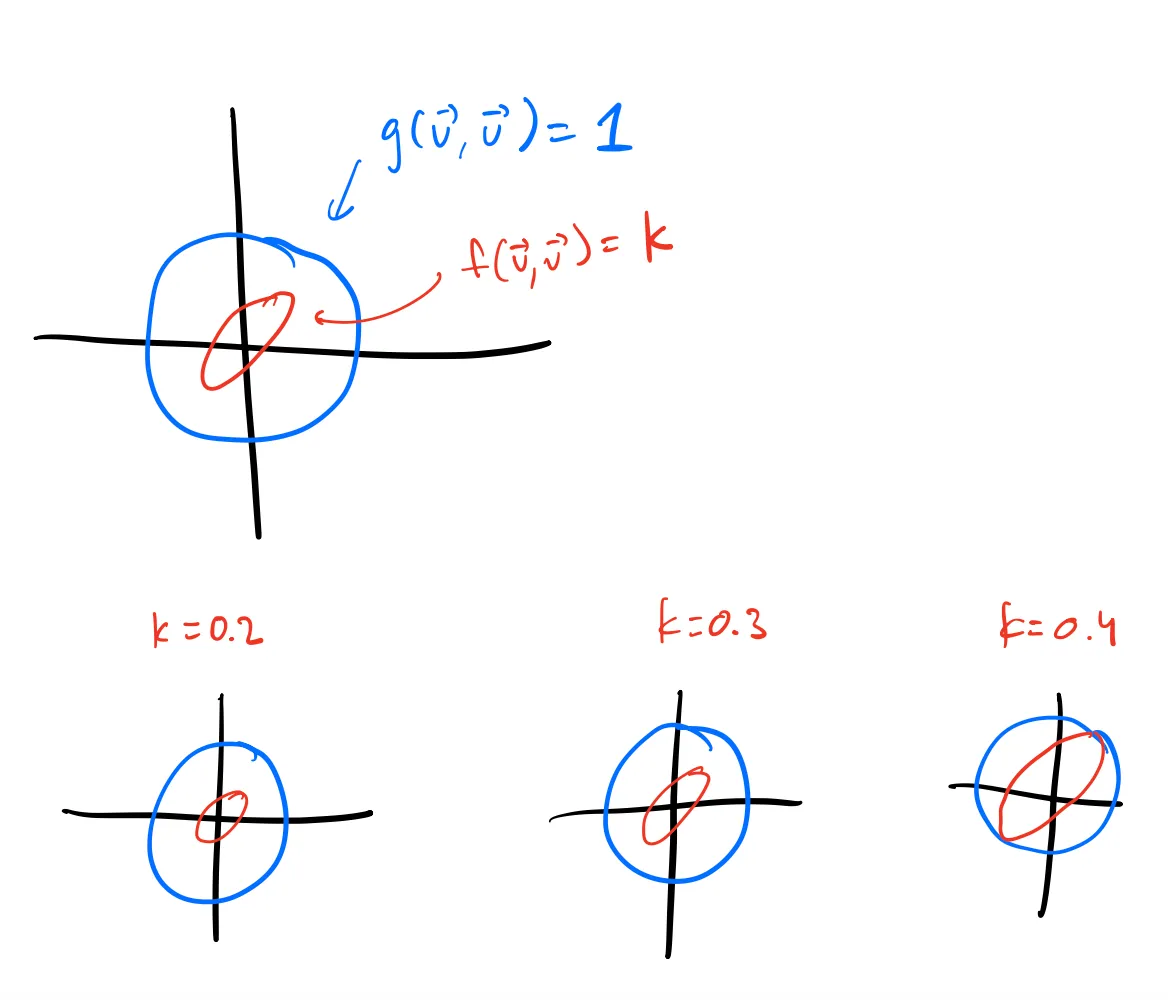

There are two concepts that we use the dot product for—magnitude and orthogonality. We can translate these ideas to any other dot product. The squared magnitude of a vector is

Geometrically, we can visualize it like this—the unit sphere of the regular dot product (the set of all points where

Note: I’m going to be ignoring positive-definiteness for most of this post; it is important at one point (see if you can figure out where), but most of the time, feel free to think of the terms “dot product” and “symmetric bilinear form” interchangeably in this post.

Mathematically, a bilinear form is completely determined by where it sends pairs of basis vectors. As a result, as a matrix, we can represent them as a “row vector of a row vector”: for example, the standard dot product on

Why? Let’s see how we calculate

Then, you can apply that to

In general, the

The symmetry property, then, means that

Currying

This matrix representation is designed for multiplying with two vectors, but there’s nothing stopping us with multiplying with one vector at a time. In fact, notice what we did with the standard dot product earlier:

It converted the

The dot product is usually viewed as a function

We call the space of all linear functions

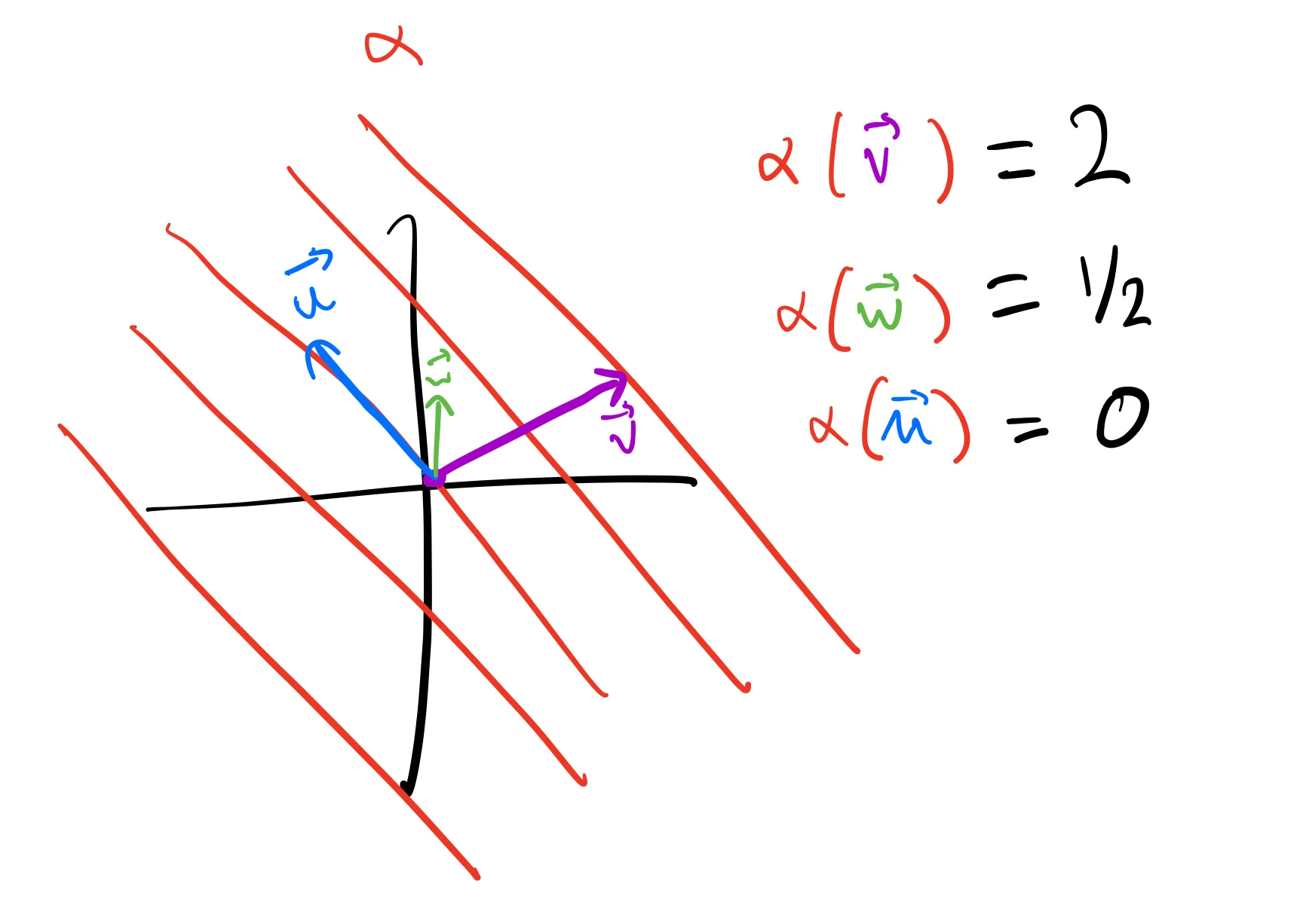

Geometrically, you can represent any covector as a set of parallel planes; then, to apply it to a vector, you count how many planes it crosses:

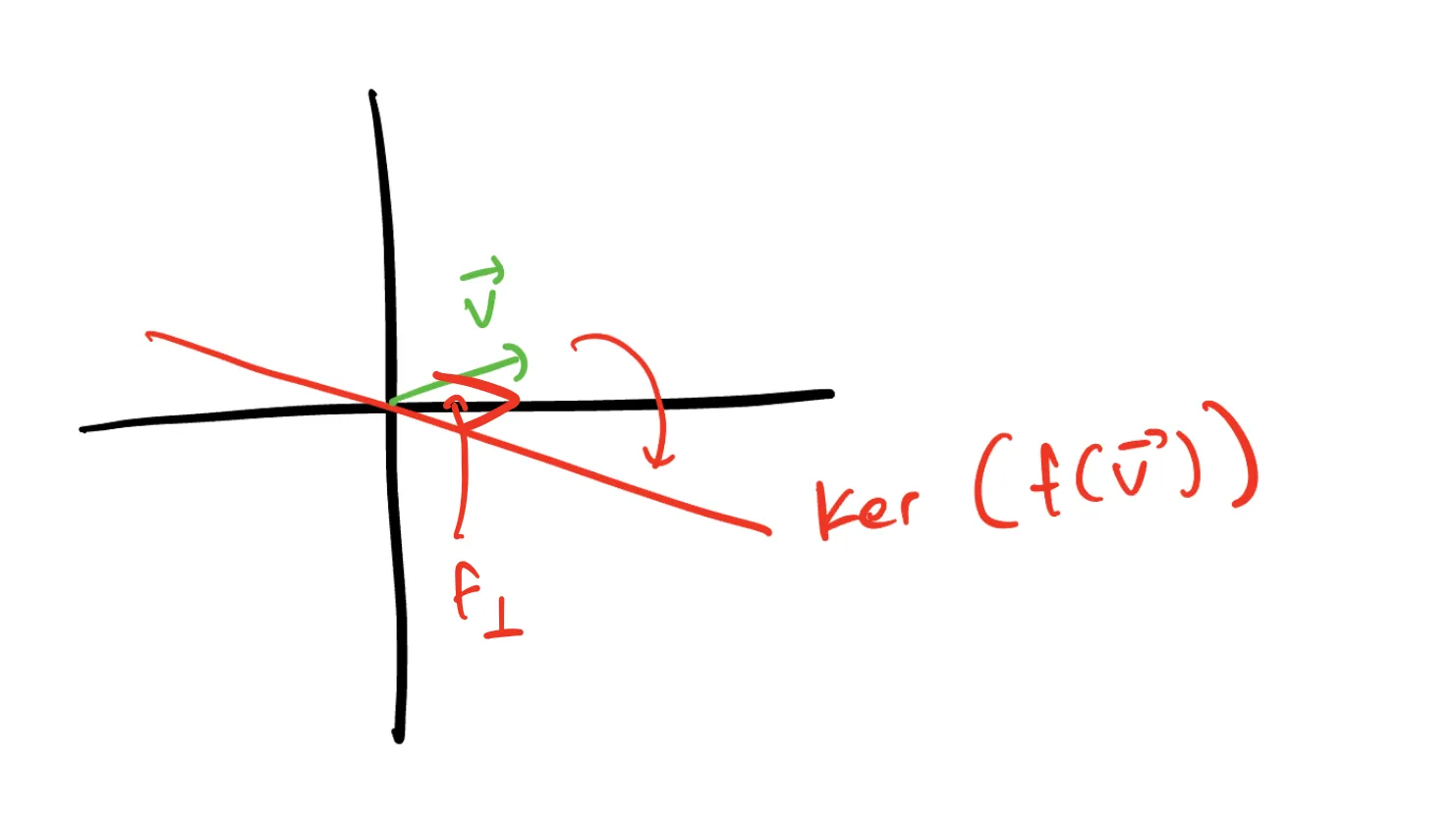

The kernel of a covector is the set of all vectors that it maps to zero. In this case, that’s represented by the plane through the origin.

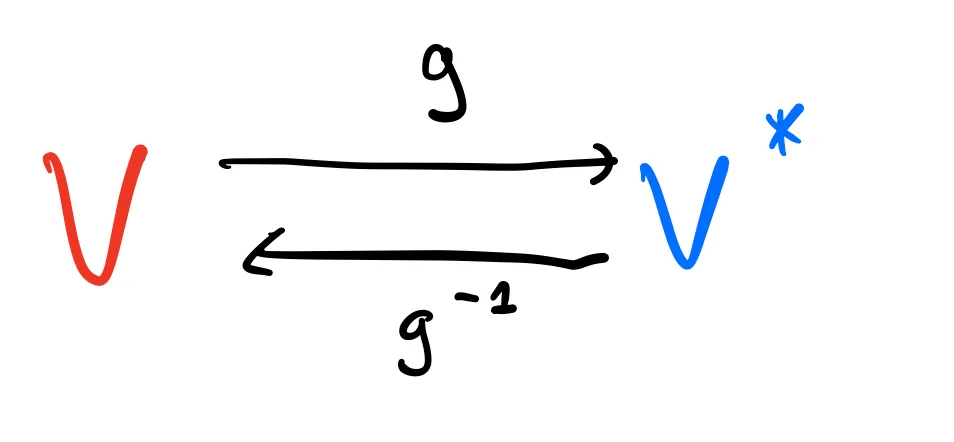

As we’ve seen, a dot product

Of course, for other dot products they won’t have such a nice representation, but in general,

Symmetric Matrices & Associated Linear Transformations

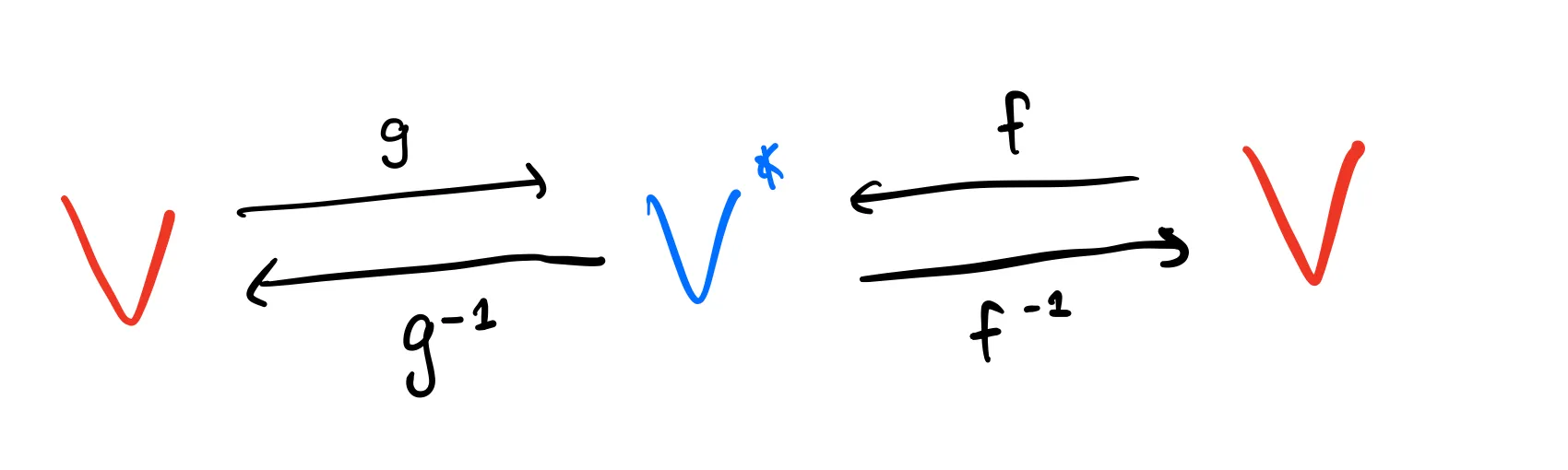

Now that we have talked about dot products, we can think about what happens if I have two of them. Let

We can think of

You can think of this by looking at the bilinear form’s matrix representation. If

We know that the symmetry property of dot products means that

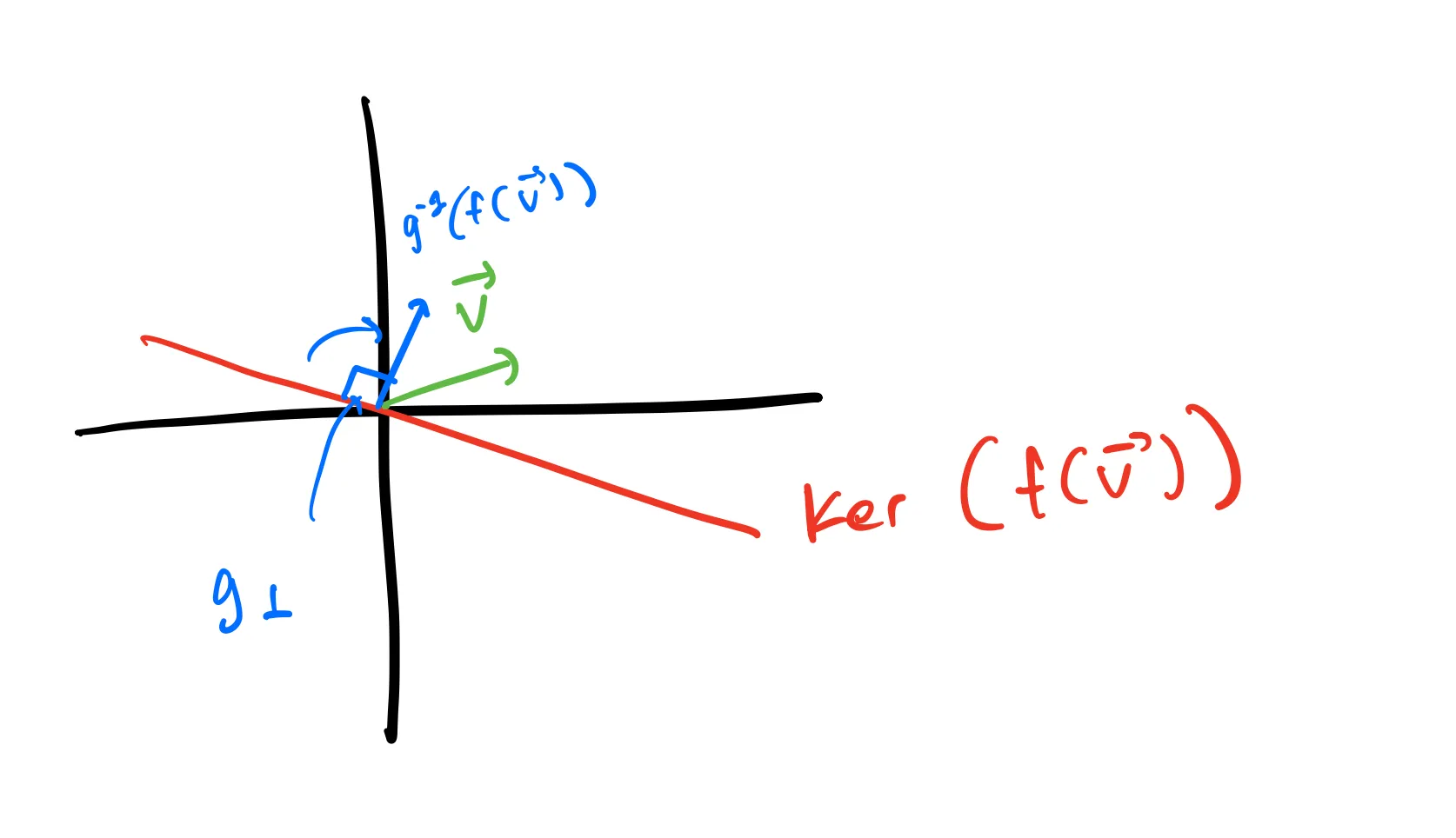

How do we think about this transformation geometrically? Well, consider that

For geometric intuition on what

Then, when we apply

Therefore, we can think of

Note:

Eigenvectors

What does an eigenvector of

The standard statement of the spectral theorem is the following: Given a dot product

If we write this in terms of

In my opinion, this is pretty nice characterization. It turns out that there’s a simple algorithm for constructing this basis, too, using the idea of maximization/minimization. Using this, we’re finally ready for the proof of the spectral theorem.

The Spectral Theorem

Consider the set of the vectors on the

The proof for this is pretty simple by using the idea of Lagrange multipliers. Imagine “blowing up” the

The minimum will be the first value of

Note: “Tangent space” actually doesn’t depend on a dot product. By definition, the tangent space of a norm

Ok, great! We’ve found one eigenvector of

Consider the set

Now, what is

What have we found? For any vector in

Now, we’re basically done! If we repeat this process recursively, finding extreme values and then restricting to their orthogonal subspaces, we will end up with a basis of

Symmetry in Real Life

This proof hinged on the fact that dot products being symmetric meant that orthogonality of vectors was a symmetric relation. I hope that makes it easier to imagine why matrices we see in nature might be symmetric—they encode some kind of symmetric relation.

I think it’s easiest to see this in the covariance case: If I have two random variables

Moment of inertia is a little harder. There are two main formulas that involve the moment of inertia in physics (three, but the third is just the time derivative of the first): In two-dimensions, we can write

If we write the kinetic energy formula using our new funny dot product notation,

The Fourier transform is also kind of hard. It’s common knowledge that the waves from the Fourier transform are the eigenfunctions of the laplacian on

because a circle has no boundary so the

As for quantum mechanical operators being Hermitian… yeah sorry I can’t help you. I think that one mostly comes from asserting the Born rule?

Anyway, those are a couple examples of where the spectral theorem would show up. There are many more (the generalized second derivative test, spectral graph theory, etc.), but I hope this article and associated proof has given an intuition for why something might be symmetric and why the spectral theorem would apply to allow you to find extreme perpendicular values.

I’ll probably make a sequel about the SVD and how it generalizes the spectral theorem not just to square normal matrices but to all linear transformations between inner product spaces.